0

There are not items in your cart.

Visit Shop

Product is not available in this quantity.

(click on images to be taken to the full article)

The Psychotomimetic Controversy of Heimia salicifolia (Sinicuichi)

As presented in the original scientific text. The content is preserved verbatim

Historical Claims and Observations

- Psychotomimetic controversy

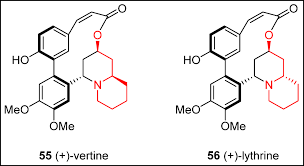

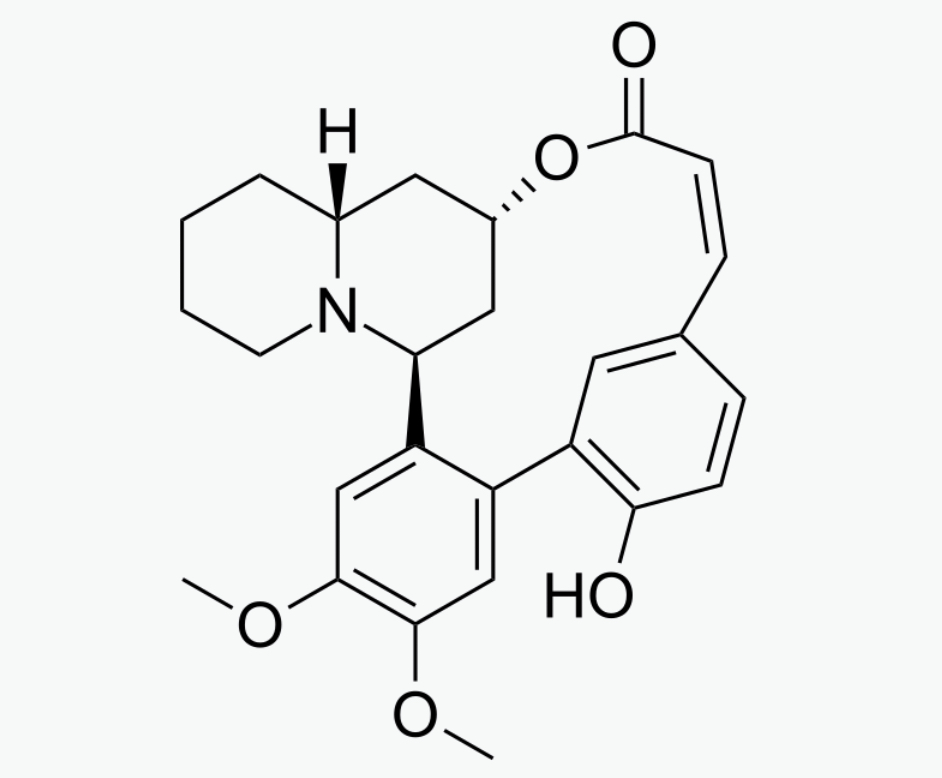

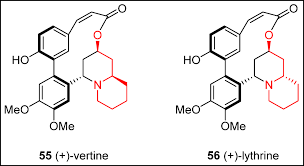

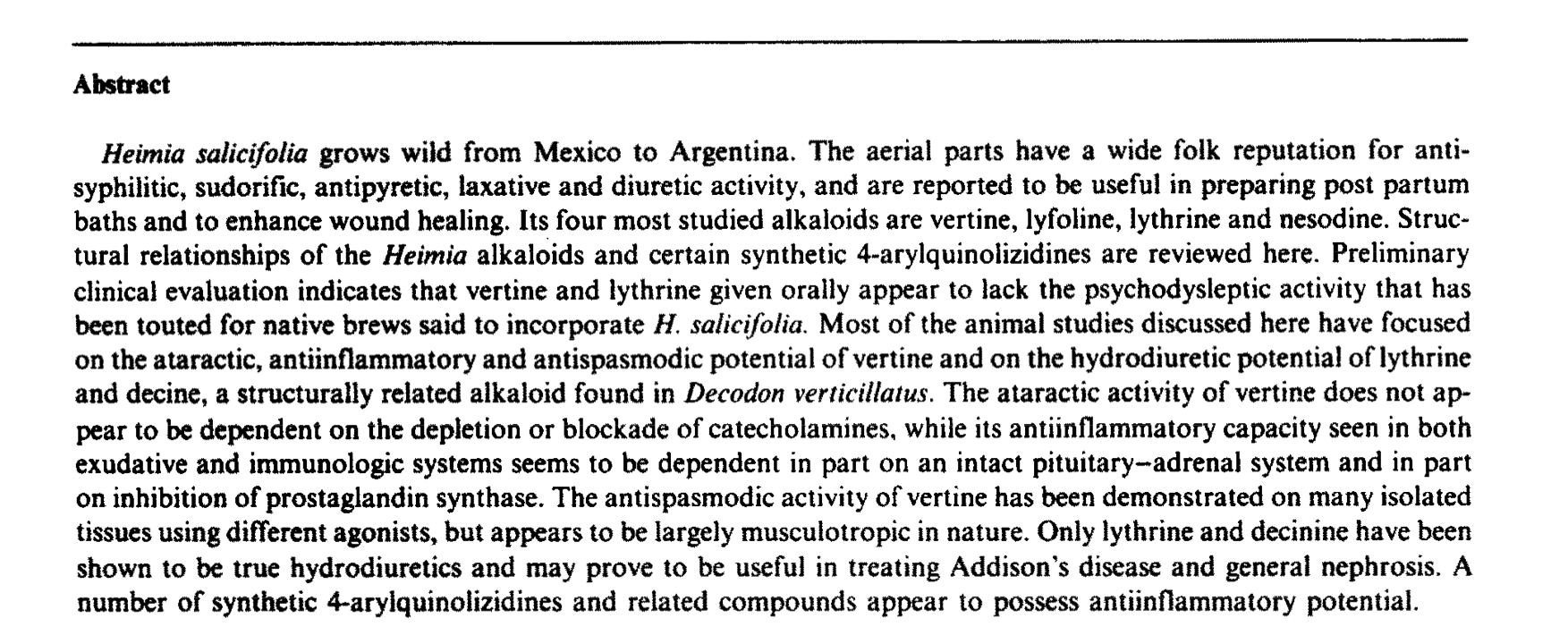

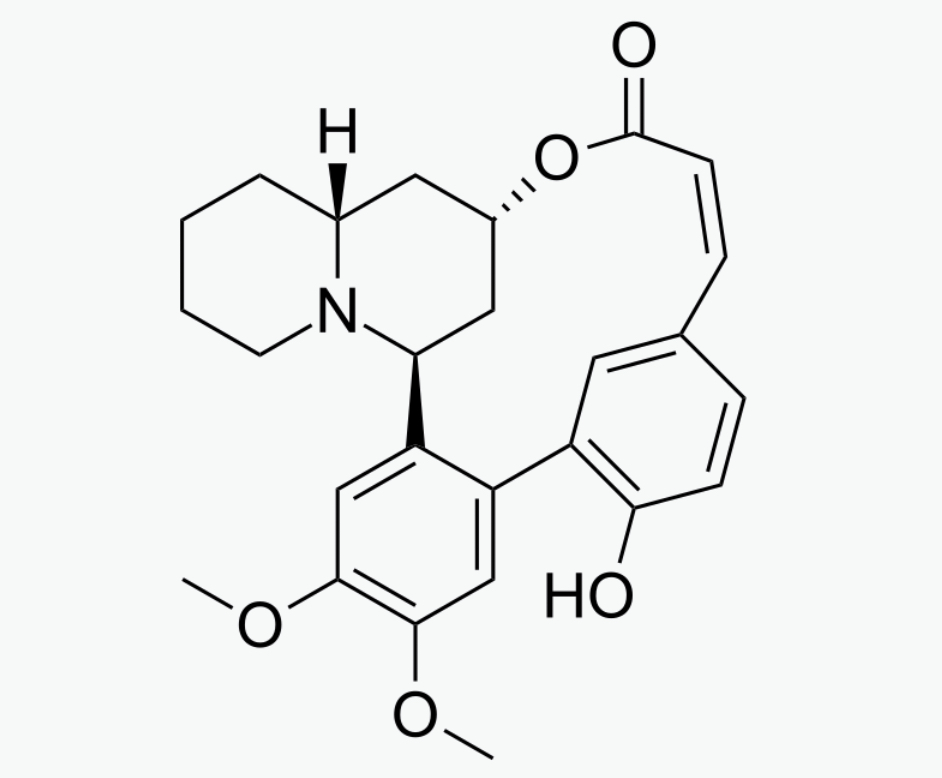

H. saiciiia also has developed a reputation in the neoscientific and scientific literature as a psychotomimetic (schizogen). This controversial attribution appears to be traceable back to a publication by Calderon (1896) who reviewed the plant’s folk medicine usage and then noted that snicuici was said to possess a ‘curious and unique physiological action . . . people drinking either a decoction or the juice of the plant have a pleasant drunkenness . . . all objects appear yellow and the sounds of bells, human voices or any other reach their ears as if coming from a long distance.’ To test this, Calderon personally ingested a series of 250-ml boiling-water decoctions prepared from 5, 10 and 15 g of H. salicifolia leaves but did not ex-perience any noticeable effects. No alterations of vision or hearing were reported. He concluded that greater doses might be needed.

Calderon’s comments were cited and then Selected synthetic compounds structurally related to the alkaloids of Heimia sulirifolia elaborated upon by Reko (1926), who apparently did not conduct any experimental or clinical studies. Reko indicated that useof the decoction ‘gives strength, energy and joy, awakens the spirit. Ob-jects are very clearly seen in great detail. Audition decreases so that ringing bells seem far away. In-dividuals feel as if walking on a soft carpet. They see a door opened but don’t hear the sound. There is nothing unpleasant, except that objects have a yellow-blue or purple sheen. Users say it is the remedy to secure happiness.’

Cultural and Terminological Confusion

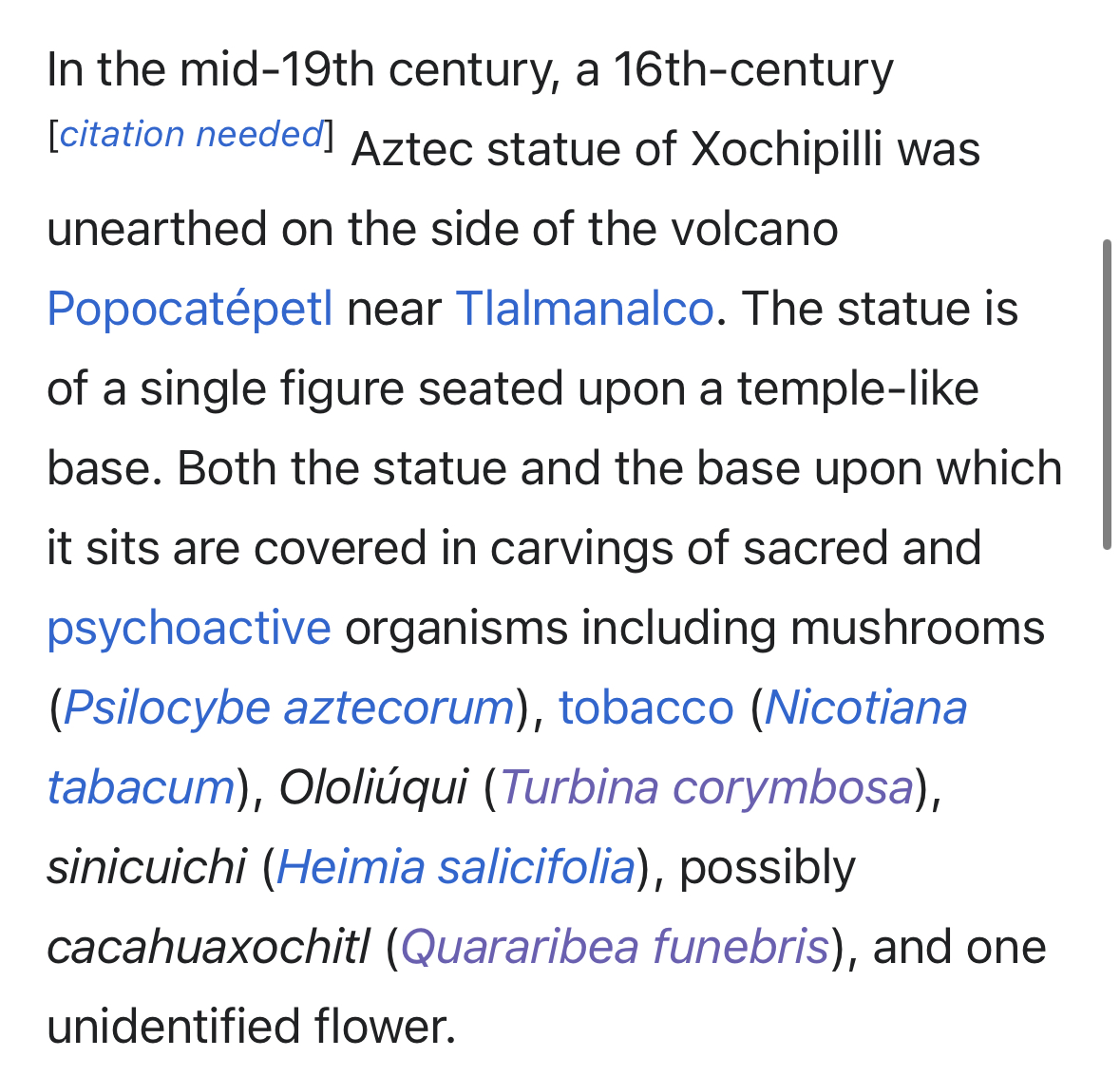

Reko (1926) further noted that the native peoples of Mexico also ex-tend the term ~~~~ to the stem and bark of Eryrhrina corafioides [Mote & Sesse] and to the bark of Piscidia erythrina L. In a later publication, Reko (1935) also clearly associated the term of ‘sinicuichi’ with the seeds of Rhynchosia praecutoriu DC. When a single common name is used for several plants, it is easy for the folk litera-ture and scientific literature to become confused. Reko (1935) further sensationalized ‘sinicuichi’ by terming it the ‘magic drink causing oblivion.’ Under its influence, users were even reputed to recall events prior to their birth (ancestral memo-ries).In 1938, Reko published a book that discuss-ed sinicuichi along with peyote, marihuana, ayahuasca and oioliqui, among others. This book went through three editions (Reko, 1949) and tended to fix H. salicifolia as sinicuichi and as a psychotomimetic in the minds of the neoscientilic and scientific communities (Schultes, 1970, 1976; Emboden, 1972; Schultes and Hofmann, 1973, 1980; Heffem, 1974; Duke, 1985). Diaz (1977) specifically classified Heimia spp. as trance-inducing psych~ysleptics and distinct from the vi-sionary psychodysleptics (mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide), imagery-inducing psychodysleptics (cannabinoids), deleriant psychodysleptics (tro-pane alkaloids) and neurotoxic psychodysleptics (Eryfhrina alkaloids, pyrrolizidines). Nevertheless, an intensive search of the scientific literature has indicated no experimental and/or clinical data to support the classification of any Heimia spp. as either psychotomimetic or psychodysleptic.

Analysis of Reported Effects

If one considers the reputed symptoms of s~nicuichi intoxication as reported by Calderon (1896) and Reko (1926), and if one discounts the variously colored vision and the ability to recall prenatal events (probably autosuggestion), the remaining effects suggest ethanol intoxication or perhaps an interaction between ethanol and a sedative principle. There is general agreement in the literature with the statement of Schultes (1976) that sinicuichi is prepared from slightly wilted leaves that ‘are crushed and soaked in water ..+ the resulting juice is put in the sun to ferment into a slightly intoxicating drink.’ This product is often fortified with other alcoholic beverages before in-gestion.It seems significant that the original study of Caldercn (1896) was negative in regard to central nervous system effects in a human after ingesting a non-alcoholic decoction equivalent to 15 g of leaves (Table 1: 1). Since that time, no other human studies have been reported in the scientific lit-erature.

Experimental Findings on AlkaloidsThe first author of this review has taken individ-ual 310-mg oral doses of vertine, lythrine and acetylsalicylic acid in a double-blind screen that coincided with a period of chronic dental pain (in-flammation associated) due to a failing root canal (Table 1:2). The three test compounds were triturated into uniform white powders before en-capsulating and coding. This dose of vertine can be considered to be equivalent to 36-l 56 g of dry aerial parts of H. salicifolia and the same dose of lythrine equivalent to 470-564 g (Rother, 1989). There was a 48-h interval between treatments. A global evaluation (in replicate) was done before in-gestion and every hour thereafter (in replicate) for the presence and absence of drug-induced symp-tomatology.

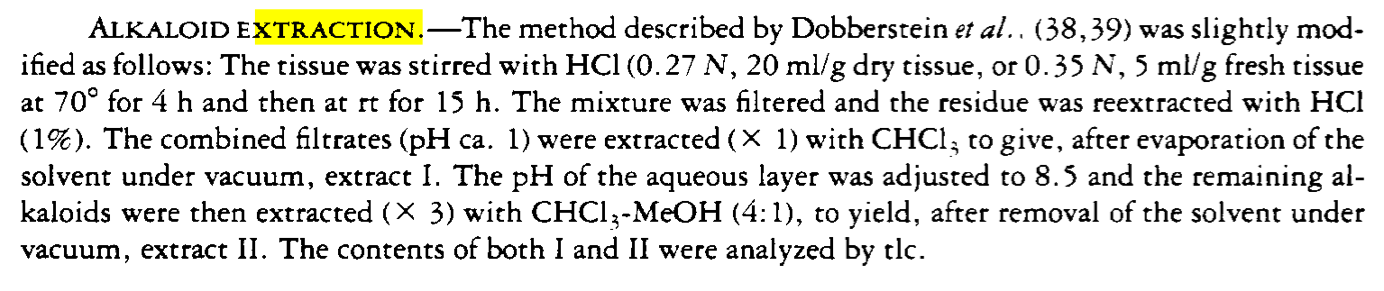

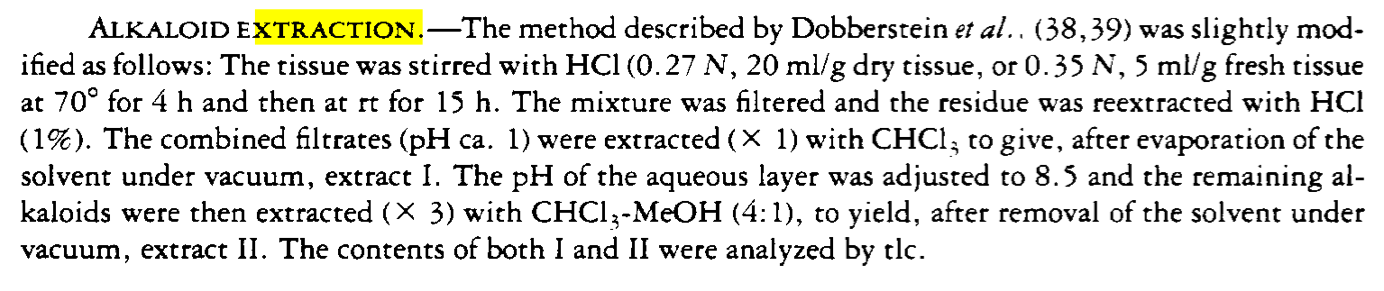

4.3. Extraction and isolation of alkaloids

Powdered leaves (1 kg) of H. salicifolia were extractedwith methanol (2 l 1 h 3). The extracts were combined and concentrated under red. pres. to give an extract (136 g). This was dissolved in 700 ml of 2% hydrochloric acid and fil- tered after 6 h. The filtrate was extracted with CHCl3 thrice and ammonia was added to adjust pH 9. This was subsequently extracted with CHCl3 several times until the CHCl3 layer showed negative to the Dragendroff’s reagent. The chloroform extract was concentrated under red. pres. to give alkaloidal fraction (12.6 g). This fraction was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (600 g – mesh 40 lm) with a gradient of CHCl3, CHCl3:MeOH (95:5), CHCl3:MeOH (90:10) and CHCl3:MeOH (80:20). Fractions, 30 ml each were pooled on the basis of TLC with Dragendroff’s reagent. This afforded five fractions A (429 mg), B (445 mg), C (1.185 g), D (1.095 g) and E (1.883 g). Fr. A subjected to CC and eluted with CHCl3:MeOH: NH4OH (95:5:0.1 v/v) afforded 3 (60 mg) and 2 (200 mg), whereas fr. B afforded 9 (92 mg), 4 (60 mg) and 5 (445 mg). Fractions, D, and E on CC under same conditions gave compounds 6 (329 mg), 1 (25 mg), 7 (30 mg), 8 (92 mg) and 9 (120 mg).

EXTRACTYION PROTOL #3

One kg of dried H. salicifolia leaves was washed, re-dried at 45 OC during 48 hours

and ground in a container. Afterwards, 4 liters of petroleum ether (J.T. Baker) were

added and the extract was obtained in 5 liters of methanol (J.T.Baker) during 24 hours.

The detection of alkaloids was carried out by adding the Dragendorff reagent.

Alkaloids were vacuum concentrated in a rotary evaporator (Buchi rotavapor model

Mp60) until having a final volume of 50 ml, then the concentrate was dried at OC for

24 hours and added to 100 ml distilled water and acidified to pH 2.0 with 10%

hydrochloric acid solution (Tec. Chem.), and filtered with aid Celite (Sigma Chem)

and the precipitate washed with distilled water. The aqueous acidic filtrate was further

defatted in a continuous extractor with 500 mL ethyl ether. The pH was adjusted to 9

with 28% ammonium hydroxide solution and the solution was extracted continuously

with 200 mL chloroform. The chloroform extract was dried in vacuo at 40OC. The

extract, dissolved in chloroform, was adsorbed on basic alumina (J.T.Baker) dried, and

placed on the top of a column (2 X 70 cm) of basic alumina (J.T.Baker). Elution was

with methanol-chloroform (1:1) and finally with methanol. The effluent collected in

three fractions was examined for alkaloid composition by thin-layer chromatographic

analysis. Each fraction was dried in vacuo and subsequently used for alkaloid isolation

using column and thin layer chromatography. The solvent mixture used was

chloroform-methanol (3:2) (5)

(click on images to be taken to the full article)

The Psychotomimetic Controversy of Heimia salicifolia (Sinicuichi)

As presented in the original scientific text. The content is preserved verbatim

Historical Claims and Observations

- Psychotomimetic controversy

H. saiciiia also has developed a reputation in the neoscientific and scientific literature as a psychotomimetic (schizogen). This controversial attribution appears to be traceable back to a publication by Calderon (1896) who reviewed the plant’s folk medicine usage and then noted that snicuici was said to possess a ‘curious and unique physiological action . . . people drinking either a decoction or the juice of the plant have a pleasant drunkenness . . . all objects appear yellow and the sounds of bells, human voices or any other reach their ears as if coming from a long distance.’ To test this, Calderon personally ingested a series of 250-ml boiling-water decoctions prepared from 5, 10 and 15 g of H. salicifolia leaves but did not ex-perience any noticeable effects. No alterations of vision or hearing were reported. He concluded that greater doses might be needed.

Calderon’s comments were cited and then Selected synthetic compounds structurally related to the alkaloids of Heimia sulirifolia elaborated upon by Reko (1926), who apparently did not conduct any experimental or clinical studies. Reko indicated that useof the decoction ‘gives strength, energy and joy, awakens the spirit. Ob-jects are very clearly seen in great detail. Audition decreases so that ringing bells seem far away. In-dividuals feel as if walking on a soft carpet. They see a door opened but don’t hear the sound. There is nothing unpleasant, except that objects have a yellow-blue or purple sheen. Users say it is the remedy to secure happiness.’

Cultural and Terminological Confusion

Reko (1926) further noted that the native peoples of Mexico also ex-tend the term ~~~~ to the stem and bark of Eryrhrina corafioides [Mote & Sesse] and to the bark of Piscidia erythrina L. In a later publication, Reko (1935) also clearly associated the term of ‘sinicuichi’ with the seeds of Rhynchosia praecutoriu DC. When a single common name is used for several plants, it is easy for the folk litera-ture and scientific literature to become confused. Reko (1935) further sensationalized ‘sinicuichi’ by terming it the ‘magic drink causing oblivion.’ Under its influence, users were even reputed to recall events prior to their birth (ancestral memo-ries).In 1938, Reko published a book that discuss-ed sinicuichi along with peyote, marihuana, ayahuasca and oioliqui, among others. This book went through three editions (Reko, 1949) and tended to fix H. salicifolia as sinicuichi and as a psychotomimetic in the minds of the neoscientilic and scientific communities (Schultes, 1970, 1976; Emboden, 1972; Schultes and Hofmann, 1973, 1980; Heffem, 1974; Duke, 1985). Diaz (1977) specifically classified Heimia spp. as trance-inducing psych~ysleptics and distinct from the vi-sionary psychodysleptics (mescaline, lysergic acid diethylamide), imagery-inducing psychodysleptics (cannabinoids), deleriant psychodysleptics (tro-pane alkaloids) and neurotoxic psychodysleptics (Eryfhrina alkaloids, pyrrolizidines). Nevertheless, an intensive search of the scientific literature has indicated no experimental and/or clinical data to support the classification of any Heimia spp. as either psychotomimetic or psychodysleptic.

Analysis of Reported Effects

If one considers the reputed symptoms of s~nicuichi intoxication as reported by Calderon (1896) and Reko (1926), and if one discounts the variously colored vision and the ability to recall prenatal events (probably autosuggestion), the remaining effects suggest ethanol intoxication or perhaps an interaction between ethanol and a sedative principle. There is general agreement in the literature with the statement of Schultes (1976) that sinicuichi is prepared from slightly wilted leaves that ‘are crushed and soaked in water ..+ the resulting juice is put in the sun to ferment into a slightly intoxicating drink.’ This product is often fortified with other alcoholic beverages before in-gestion.It seems significant that the original study of Caldercn (1896) was negative in regard to central nervous system effects in a human after ingesting a non-alcoholic decoction equivalent to 15 g of leaves (Table 1: 1). Since that time, no other human studies have been reported in the scientific lit-erature.

Experimental Findings on AlkaloidsThe first author of this review has taken individ-ual 310-mg oral doses of vertine, lythrine and acetylsalicylic acid in a double-blind screen that coincided with a period of chronic dental pain (in-flammation associated) due to a failing root canal (Table 1:2). The three test compounds were triturated into uniform white powders before en-capsulating and coding. This dose of vertine can be considered to be equivalent to 36-l 56 g of dry aerial parts of H. salicifolia and the same dose of lythrine equivalent to 470-564 g (Rother, 1989). There was a 48-h interval between treatments. A global evaluation (in replicate) was done before in-gestion and every hour thereafter (in replicate) for the presence and absence of drug-induced symp-tomatology.

4.3. Extraction and isolation of alkaloids

Powdered leaves (1 kg) of H. salicifolia were extractedwith methanol (2 l 1 h 3). The extracts were combined and concentrated under red. pres. to give an extract (136 g). This was dissolved in 700 ml of 2% hydrochloric acid and fil- tered after 6 h. The filtrate was extracted with CHCl3 thrice and ammonia was added to adjust pH 9. This was subsequently extracted with CHCl3 several times until the CHCl3 layer showed negative to the Dragendroff’s reagent. The chloroform extract was concentrated under red. pres. to give alkaloidal fraction (12.6 g). This fraction was subjected to column chromatography on silica gel (600 g – mesh 40 lm) with a gradient of CHCl3, CHCl3:MeOH (95:5), CHCl3:MeOH (90:10) and CHCl3:MeOH (80:20). Fractions, 30 ml each were pooled on the basis of TLC with Dragendroff’s reagent. This afforded five fractions A (429 mg), B (445 mg), C (1.185 g), D (1.095 g) and E (1.883 g). Fr. A subjected to CC and eluted with CHCl3:MeOH: NH4OH (95:5:0.1 v/v) afforded 3 (60 mg) and 2 (200 mg), whereas fr. B afforded 9 (92 mg), 4 (60 mg) and 5 (445 mg). Fractions, D, and E on CC under same conditions gave compounds 6 (329 mg), 1 (25 mg), 7 (30 mg), 8 (92 mg) and 9 (120 mg).

EXTRACTYION PROTOL #3

One kg of dried H. salicifolia leaves was washed, re-dried at 45 OC during 48 hours

and ground in a container. Afterwards, 4 liters of petroleum ether (J.T. Baker) were

added and the extract was obtained in 5 liters of methanol (J.T.Baker) during 24 hours.

The detection of alkaloids was carried out by adding the Dragendorff reagent.

Alkaloids were vacuum concentrated in a rotary evaporator (Buchi rotavapor model

Mp60) until having a final volume of 50 ml, then the concentrate was dried at OC for

24 hours and added to 100 ml distilled water and acidified to pH 2.0 with 10%

hydrochloric acid solution (Tec. Chem.), and filtered with aid Celite (Sigma Chem)

and the precipitate washed with distilled water. The aqueous acidic filtrate was further

defatted in a continuous extractor with 500 mL ethyl ether. The pH was adjusted to 9

with 28% ammonium hydroxide solution and the solution was extracted continuously

with 200 mL chloroform. The chloroform extract was dried in vacuo at 40OC. The

extract, dissolved in chloroform, was adsorbed on basic alumina (J.T.Baker) dried, and

placed on the top of a column (2 X 70 cm) of basic alumina (J.T.Baker). Elution was

with methanol-chloroform (1:1) and finally with methanol. The effluent collected in

three fractions was examined for alkaloid composition by thin-layer chromatographic

analysis. Each fraction was dried in vacuo and subsequently used for alkaloid isolation

using column and thin layer chromatography. The solvent mixture used was

chloroform-methanol (3:2) (5)